Perspective Drawing - Using a Central Eye Level

This lesson illustrates how a central eye level is useful when you wish to create an equal balance between the sky and foreground of a landscape.

(swipe the image back and forward to view)

A central eye level is useful where you wish to create an equal balance between the sky and foreground in a landscape.

-

Wherever you choose to place the eye level/horizon in a picture will have a crucial effect on its composition.

-

If you can see or if you know the position of the horizon in a picture, the image automatically becomes an extension of your own personal space.

-

As the horizon is also your eye level, you can understand the scale and space of the image in relation to your own body. Any part of the image which is in line with the eye level feels as if it is close to your own personal height. This effect works whether objects are small or large, near or far, or whether the viewer is standing, sitting or lying down.

Famous Artworks with a Central Eye Level

JAN VERMEER (1632-1675)

'The Kitchen Maid', 1658 (oil on canvas)

(Click on the flip icon to view)

The orthogonal window frames in this painting meet on the eye level which is just above the kitchen maid's hand and their vanishing point leads us directly into to the motion of the pouring milk (click on the flip icon to view). Note how the angle of her head and shoulders is a perfect reflection of the angle of the orthogonal window frames, again emphasizing the shape and direction of the flowing milk within the wider scale of the composition. The eye level in this painting suggests that the scene is observed from a seated position which enhances the quiet and pensive atmosphere of the work.

JOHN CONSTABLE (1776-1837)

'Flatford Mill', 1817 (oil on canvas)

(Click on the flip icon to view)

Constable uses a centrally positioned eye level to create a balanced composition where all elements of the subject - figures, foreground, trees and sky - are of equal importance to its design. If you click on the flip icon below the image you can see how Constable has focused on these specific elements in each 'quarter' of the painting.

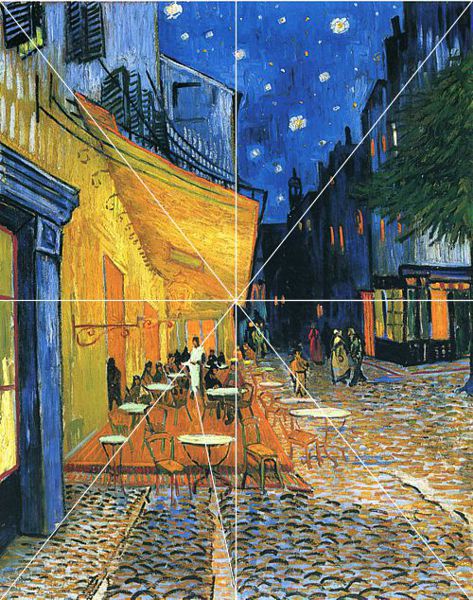

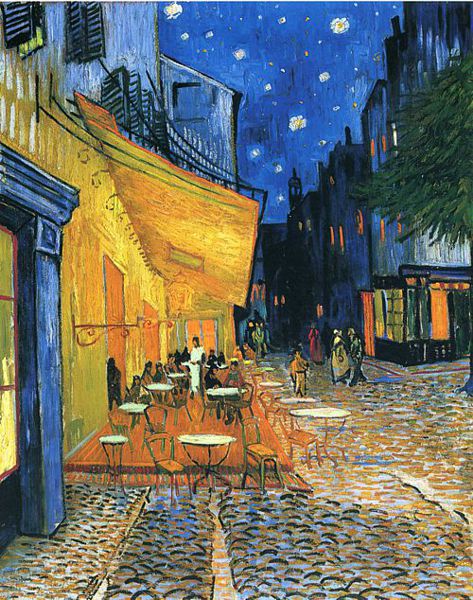

VINCENT VAN GOGH (1853-90)

'The Cafe Terrace at Night', 1888 (oil on canvas)

(Click on the flip icon to view)

The diagonals of this painting loosely form the lines of perspective which meet on the eye level at the centre of the picture (Click on the flip icon to view). It is a simple composition that divides the image diagonally into star-lit and lamp-lit sections. Note how Van Gogh cleverly redirects the angle of the central gutter to lead our eye to the focal point of the waiter in white who is almost overpowered by the yellow canopy and its ambient light. This is a bold example of one-point perspective.

GUSTAVE CAILLEBOTTE (1848 -1894)

'Paris Street, A Rainy Day', 1877 (oil on canvas)

(Click on the flip icon to view)

Paris Street, A Rainy Day is an excellent example of how to use a central eye level.

In this scene, the viewer shares the same eye level as the strolling figures. This creates the strong illusion that you are walking or standing on the same street. The common eye level forms a spatial link between you and the other figures and psychologically you feel that you are part of the scene. The picture frame becomes your field of vision and you almost get the sense that you need to step aside to avoid brushing shoulders with the approaching gentleman.

This intimate relationship between the viewer and the image is what makes the work so popular. It is like taking a look through a window in time.

The painting is very carefully arranged. The strong eye level divides the picture horizontally, while the lamp-post and its reflection bisect it vertically. These lines intersect at the central vanishing point, creating four rectangles, each of which contributes a separate element to the composition of the painting (Click on the flip icon to view this structure):

1) The lower right rectangle with the boldest shapes and strongest contrasts, establishes the foreground.

2) The lower left rectangle, with its triangular arrangement of figures that echo the shape of the building above, stakes out the middle ground.

3) The upper right rectangle links the foreground and background as the buildings recede in sequence from behind the umbrellas.

4) The upper left rectangle provides the main background interest with both sides of an apartment block viewed in dramatic perspective.

It is hard to avoid the idea that the shapes which fill the upper rectangles are subconsciously influenced by Caillebotte's training as a naval architect. The apartment block on the left is like the bow of a massive ship steaming towards the viewer. If you continue the analogy, the umbrellas on the right suggest the wind-filled forms of sails bobbing about on the sea of wet cobblestones. Yachting, after all, was one of the main pastimes to which Caillebotte returned when he gave up painting in later life.

In common with the Impressionists, Caillebotte captured the everyday scenes of urban Paris, usually from a middle class viewpoint. In Paris Street, A Rainy Day, painted in 1887, he portrays the new look of the city at the end of the 19th century when Baron Georges Haussmann regenerated the old Paris of narrow streets and alleys. He replaced these with the network of wide boulevards that characterise Paris to this day. In this painting, the grid-like arrangement of the space and the radial frames of the umbrellas evoke the arterial structure of this new road system.