Paintings by Rembrandt

Rembrandt van Rijn is one of the greatest masters in the history of art and the outstanding Dutch painter of the 17th century. It is his underlying compassion for people as they are, for better or worse, that make his art both timeless and universal.

Rembrandt van Rijn is one of the greatest masters in the history of art and the outstanding Dutch painter of the 17th century. Most Dutch artists specialized in specific genres such as portraiture, landscapes, still life or history paintings. Rembrandt stood apart from his contemporaries as he embraced most of these subjects, but their prevailing mood was always filtered through a sensitivity that acknowledged the flaws and frailty of the human condition. It was this underlying compassion for people as they are, for better or worse, that make his art both timeless and universal.

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606 -1669)

'The Artist in his Studio', c.1628 (9.75in. x 12.5in.) oil on panel.

Rembrandt was born on 15th July 1606, the eighth of nine children, into a lower middle- class family from the university town of Leiden. His father, Harmen, was a miller and his mother, Cornelia was a baker’s daughter. It is assumed that he was the brightest of his siblings as he attended the Leiden Latin school while his brothers were apprenticed to trades. This gave him a grounding in classical history and literature that he later incorporated into his paintings. At the age of 14 he enrolled at Leiden University, one of the top educational establishments in Europe, but left after several months to take up an apprenticeship with a local painter, Jacob Isaaxszoon van Swanenburgh. In 1625, he moved to Amsterdam to work with Pieter Lastman, one of the leading painters in the country, but again left after six months to set up a studio in Leiden with his friend Jan Lievens, another of Lastman's students.

'The Artist in his Studio' is a tiny painting that captures all the hope and ambition of the young Rembrandt as he strikes out on his own. The small figure of the artist stands in his crumbling studio, holding his brushes and a maulstick, considering the large painting on the easel before him. A couple of palettes are nailed to the wall to set the scene. However, it is the painting, not the artist, that is the focal point of this work. We cannot see what he has painted as we view the easel and painting from the back, but what we can see is the radiant light that bounces off its surface to illuminate the room – a symbol of the enlightenment that art offers the viewer. The laser-light edge to the painting highlights the energy of the work as the artist basks in the reflected glory of his creation. He uses the idea of a painting within a painting to frame his concept: the panel that Rembrandt painted is very small, but it depicts a painting about 20 times larger, an allusion to the power of art in the imagination. This small picture is a big statement of the artist's determination to succeed in his craft.

Rembrandt's Early Portraits

- rembrandt-self-portrait-in-a-cap

Self Portrait in a Cap (1630)

-

Self Portrait Frowning (1630)

- rembrandt-self-portrait-shouting

Self Portrait Shouting (1630)

- rembrandt-beggar-sitting-on-a-bank

Beggar Sitting on a Bank (1630)

- old-man-with-beard

Old Man with a Beard (1630)

- rembrandts-mother

The Artist's Mother (1628)

Rembrandt’s early work consisted mainly of drawings and etchings of friends, family and locals with faces full of character. He used these studies, many of which focus on facial expression, as source material for his paintings and etchings. The three self-portraits in our slide show above explore a range of expressions that respectively convey emotions of 'surprise', 'disapproval' and 'anger'. In the image that follows them, you can see how Rembrandt has used this knowledge as he grafts his own head onto the body of a beggar. He completely understands how to capture and adjust the mood of a figure through its body language and facial expression. The portraits of the 'Old Man with a Beard' and the 'Artist's Mother' reveal Rembrandt's fascination with the face as its flesh yields to the aging process, a theme that prevails throughout his entire body of work. The old man's bowed head and furrowed brow reveal a melancholic character, while his mother's weathered features convey a dignified perseverance in the face of life's hardships.

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606 -1669)

'Self Portrait', 1629 (oil on panel)

Rembrandt's small 'Self Portrait' of 1629 is usually seen as the first in a series of self-portraits that chronicle his changing fortunes and illustrate his growth as an artist. Apart from his fellow Dutchman, Vincent Van Gogh, no other artist charts his own development with such introspective honesty.

This early work introduces us to Rembrandt's use of shadows, which initially appear dark and vague, but once you slow down and adjust your vision, their subtle details gradually emerge from the darkness. The rich depth of color and observation that is concealed in Rembrandt's shadows is one of the main qualities that characterise his work.

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606 -1669)

'Detail from Self Portrait', 1629 (oil on panel)

Another distinctive quality that is evident here is the vitality of his brushwork. Not only does he build up the solid detail of his shirt collar with a raised impasto, but he also creates the curls in his hair by scratching them into thick wet paint with the pointed handle of his brush.

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606 -1669)

'Portrait of Nicolaes Ruts', 1631 (oil on panel)

In the 17th century, Amsterdam was the hub of the Dutch trading routes, importing and exporting goods from around the world. As it grew into the most prosperous port in Europe, its rich merchants decorated their houses with exotic imports from abroad and immortalized their success by having their portraits painted. Rembrandt recognized the potential of this market and moved to the city in 1631. He quickly gained the position of head painter in the studios of Hendrick van Uylenburgh, an art dealer who worked as an agent to arrange commissions for the artists in his employ.

The work that made Rembrandt's reputation as the painter of choice to the wealthy burghers of Amsterdam was his 'Portrait of Nicolaes Ruts' (1573-1638), a merchant in the fur trade. It was his first major commission and the ideal subject to demonstrate his skills to the market. Rembrandt portrayed the merchant as an astute businessman, expensively attired in a fur hat, crisp white ruff and an extravagant sable-trimmed robe. This was the perfect branding image with the retailer modelling his own product. He typecast Ruts as prosperous on one hand, but prudent on the other; an attractive blend to the Dutch patrons whose Protestant faith expected moderation in their business ethics. His dark figure stands out against a dark background, illuminated by its radiant aura, only to be eclipsed by the exquisite painting of his head, hands and fur robe. The mercantile class could not resist such a positive makeover and flocked to Rembrandt’s studio in their droves. Over the next couple of years his output was extraordinary, painting on average a portrait a month.

Dutch Group Portraits

Pieter Pieterz (1540-1603)

'The Six Wardens of the Drapers Guild', 1599 (oil on canvas)

As Rembrandt's reputation grew he was offered lucrative commissions to paint group portraits which were popular with Amsterdam's merchant and militia guilds. Traditional guild portraits like 'The Six Wardens of the Drapers Guild', were decidedly dull pictures that did little more than document their conventionally dressed executives, much in the same manner as a boardroom photograph today.

The more flamboyant militia guilds had a larger membership, where everyone had the opportunity to pay for his own portrait. This meant that the artist often had one or two dozen figures to arrange in a unified composition, with the added complication of distinguishing the officer class from the ranks. The 'De Meagre Company' painting, which was started by Franz Hals and finished by Pieter Codde, was the traditional solution to this problem, where the figures were lined up in a row with the officers identified by their more colorful attire.

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606 -1669)

'The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp', 1632 (oil on canvas)

(Drag the arrow to reveal the composition structure)

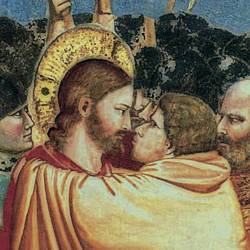

In 'The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp', Rembrandt breathed new life into the genre of Dutch group portraits with a Baroque arrangement that turned the usual documentary image into a dramatic scene.

As the Praelector Anatomiae (Professor of Anatomy) and the most distinguished surgeon, Dr. Tulp occupies the entire right half of the painting. He also wears a big black hat lest there be any doubt. Rembrandt ingeniously arranges six of the seven guild members into an arrowhead formation that leads our eye to the focal point of the picture (drag the arrow on the left of the painting to reveal its composition structure). Here Dr. Tulp tweaks a flexor in the corpse's forearm with a pair of forceps, while he simultaneously twists his wrist to illustrate the mechanics of the movement. The seventh member of the guild, who is situated directly to Dr. Tulp’s left, holds a sheet of paper with the names of all the members present in the portrait. Rembrandt emphasizes the form of each individual with a dramatic chiaroscuro that illuminates the dark operating theatre and spotlights the group.

Dr. Tulp was the head of the Amsterdam Guild of Surgeons and one of his annual duties was to perform a public dissection. This was a tradition established by the 16th century anatomist, Andreas Vesalius, whose classic book De Humani Corporis Fabrica, 1543 (On the Fabric of the Human Body) sits at the feet of the cadaver. These anatomy lessons could continue for up to three days, after which the stench of the decomposing body made the work unbearable. As a rule, they generally took place in the cold months of winter due to a lack of refrigeration. This one can be dated to 31st January 1632 as Adriaan Adriaanszoon (aka 'Aris Kindt'), the corpse on the table, was executed earlier that day for armed robbery. By law the subject for dissection had to be male and an outcast from the Church.

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606 -1669)

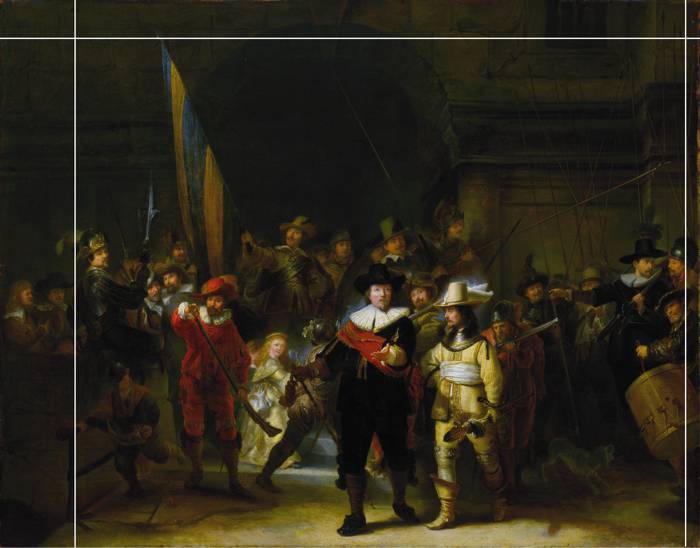

'The Night Watch', 1642 (oil on canvas)

In 1640 Rembrandt was commissioned to paint a group portrait of The Kloveniers Company, one of the many militia guilds that were formed to protect Dutch cities from the Spanish during the War of Independence (The Eighty Years' War). By Rembrandt's time, these groups were no more than ceremonial guilds where the participants enjoyed a good meal and a rollicking march. The original title of the painting was 'The Militia Company of Captain Banning Cocq' but by the end of the 18th century, it was renamed 'The Night Watch' as its varnish had darkened so much with time and grime that people believed the scene took place at night. Although this was inaccurate, the new title stuck as it had much more impact and appeal.

If 'The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp' adds a touch of theatre to the tradition of Dutch group portraits, 'The Night Watch' is its epic drama. Rembrandt flips genres to turn a dull regimental line-up into a striking history painting alive with noise and movement. He captures the moment when Captain Frans Banning Cocq invites his lieutenant, Willem van Ruytenburch, to lead off the Kloveniers. The entire militia bristles with pikes and halberds and the air is charged with excitement as the march is set in motion. The drummer beats out the pace of the march while the standard bearer raises the company flag. The musketeers prepare their klovers (a type of musket) for action: one is depicted loading his gun; another blows off the excess gunpowder from the lock; and a third, partially hidden behind Banning Cocq, recklessly fires off a shot. Unlike traditional militia portraits, Rembrandt adds some extra (non-paying) characters for dramatic effect. On the left a young boy (a powder monkey) runs to assist a musketeer; on the right a dog barks in the confusion; and in the middle an enigmatic little girl with a dead fowl tied to her waist (probably a reference to the Captain's name), illuminates the darkness with a mysterious light that seems to glow from within her.

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606 -1669)

Detail from 'The Night Watch', 1642 (oil on canvas)

The 'Night Watch' is just under 12ft high with life size figures that appear to share the same ground plane as the viewer. Banning Cocq, dressed in black with a bold red sash, takes a step towards the viewers’ space and motions the militia forward with his superbly foreshortened hand. This gesture holds additional layers of meaning: on one hand it seems to invite the viewer into the painting; on the other it casts a shadow on van Ruytenburch’s jacket, pinching the embroidered symbol of a lion (from the Amsterdam coat of arms) between the thumb and forefinger - a metaphor that the safety of the city is in the hands of the Kloveniers.

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606 -1669)

Composition of 'The Night Watch', 1642 (oil on canvas)

The forward movement of the company is reinforced by the angle of van Ruytenburch's ceremonial lance, another demonstration of Rembrandt's skilful draftsmanship. To superimpose a sense of order within the hustle and bustle for position, Rembrandt arranges the angles of several weapons like parallel rows of stitching to link the different elements of the group and pull the composition together. He then employs a strong frontal light source which varies in its intensity, shining with greater magnitude on certain figures to highlight their importance. The exception to this is the mysterious little girl who seems to generate her own ethereal light. As she has the face of Rembrandt’s wife, Saskia, who died in 1642 just before the painting was completed, it is more than possible that this was his way to commemorate her passing.

When we first look at the painting, our natural curiosity takes over as we scan the group to discover the part that each figure plays within the chaotic assembly. Rembrandt had the exceptional ability to capture the expression and body language of an individual to reveal their natural character, but it was said that some of the company were dissatisfied with their own personal likeness - a justifiable complaint if you had paid for your portrait to be included. This, however, did not bother Rembrandt, as he was more concerned that each figure in ‘The Night Watch’ had an individual personality that contributed to the overall composition.

Gerrit Lundens (1622-83)

Copy of 'The Night Watch', 1642 (oil on oak panel)

The 'Night Watch' was first hung in the Great Hall of the 'Kloveniersdoelen' (the musketeers' headquarters and shooting range), where the walls were decorated with group portraits of the different militia guilds. It remained there for over 70 years, but in 1715 when it was moved to the new Amsterdam Town Hall, the authorities committed a crass act of artistic vandalism to make it fit into a space between two doors: they lopped 2 ft. off the left-hand side, about 1ft. from the top, and thinner strips from the right-hand side and the bottom. We can get some idea of its original composition from a small copy of the painting by Gerrit Lundens (1622-83), which was probably commissioned by Frans Banning Cocq.

By 1889, when it was rehoused in the Rijksmuseum, it was a national icon and allocated the most prominent space in the gallery. It is a testament to Rembrandt's genius that, despite the vandalism, many consider ‘The Night Watch’ to be the greatest painting of the Dutch Golden Age.

Rembrandt's Pupils and Assistants

Which is the Copy?

Drag the bar and make your choice. You will find the *answer in the text below.

'Rembrandt Self Portrait', 1629 (oil on canvas)

As the most famous artist in Amsterdam, Rembrandt attracted many pupils and assistants. This was not from any noble desire to share his knowledge of art, but more out of necessity as their considerable fees helped to offset his expenditure. As Rembrandt's income increased, his extravagance outstripped his earnings as he indulged his passion for collecting art, antiques and rare objects. He was a compulsive collector amassing rooms full of paintings, around 8000 drawings and prints by famous artists, classical sculptures, antique weapons and armour, musical instruments, geographical globes, maps and books, vintage textiles and costumes, Venetian glass and exotic natural history objects. He spent vast sums of money on his collection which became an emotional addiction rather than commercially motivated dealing.

Working in Rembrandt's studio was a prestigious position that appealed to the best young artists from around the country, including Samuel van Hoogstraten, Gerard Dou, Gerbrand van den Eeckhout, Gerrit Willemsz Horst, Carel Fabritius, Nicolaes Maes, and many others who went on to become acclaimed painters of the Dutch Golden Age. Not only were they tutored by the greatest painter of the age, but they also had access to his remarkable collection as source material for their work.

Pupils and assistants both copied his works and imitated his style of painting. Without any concerns over the regulation of copyright or ownership, it is believed that Rembrandt signed or 'autographed' the best examples of their art to enhance their market value. However, in museums around the world today, this unfortunate practice has created a lot of uncertainty about many of the Rembrandt's in their collections. As a greater awareness of the characteristics of the artist’s style has shed light on the authenticity of his work, many paintings previously attributed to Rembrandt have now been discredited.

Follower of Rembrandt van Rijn

'The Man with the Golden Helmet', c.1650 (oil on canvas)

The Rembrandt Research Project is the feared body of experts that authenticates the artist's work and in recent years formerly accepted masterpieces such as 'The Man with the Golden Helmet' and one of the two self-portraits above, have been demoted to the status of a 'follower' or 'copy' of Rembrandt.

*Answer: The genuine Rembrandt above is the 'Self-Portrait in a Gorget' (1629) from the Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg which was originally thought to be a copy. The copy, which was originally thought to be the genuine article, is from The Mauritshuis collection in The Hague.

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606 -1669)

'Saskia van Uylenburgh in Arcadian Costume', 1635 (oil on canvas)

In 1634, Rembrandt met and married Saskia van Uylenburgh, the 21-year-old niece of his art dealer patron, Hendrick van Uylenburgh. Orphaned by the age of 12, she was from a higher social class than Rembrandt and of independent means due to a legacy from her parents. They lived with van Uylenburg for about a year before leaving his employ and renting a house/studio in the fashionable Nieuwe Doelenstraat. As Rembrandt’s fame and fortune grew, he pushed the boat out to purchase a grand four storey house in Sint Antoniesbreestraat, now the Rembrandt House Museum, which, coincidentally, was next door to van Uylenburgh's studios.

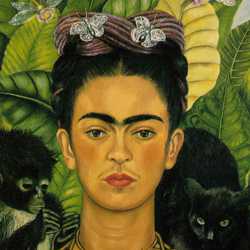

'Saskia van Uylenburgh in Arcadian Costume' is one of several images of Rembrandt's wife where she is dressed in a spectacular costume, probably selected from the artist's extensive collection of antiques. Here Saskia is portrayed as Flora, the Roman goddess of flowers and springtime. Such Arcadian themes were popular at that time in Holland, featuring often in both art and literature.

There are no first-hand accounts of Rembrandt's relationship with Saskia, but you can tell from the sensitivity of her portraits that he adored her. Although she represents a conventional Roman deity, she does not conform to the typical depictions of 'Flora' in art, as personified by Botticelli's graceful images of Simonetta Vespucci, the Renaissance equivalent of a super model. Rembrandt reveals a greater beauty that speaks from within; he mirrors the kindness and tenderness that he sees in Saskia so that we may see the person he loves.

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606 -1669)

Detail from 'Saskia van Uylenburgh in Arcadian Costume', 1635 (oil on canvas)

On a technical level, this painting is stunning. He builds up layer upon layer of thick over thin and light over dark paint, until it reaches a depth of tone, color and texture that have an intensity and integrity unique to Rembrandt. His painting technique is never laboured. It has a breathtaking confidence and certainty of touch that asserts the authority of his genius.

Despite the success and prosperity that he achieved in the 1630s, within seven years from the completion of this work, Rembrandt's world would fall apart. Between 1635 and 1640, Saskia gave birth to three children, a son Rumbartus and two daughters both named Cornelia, all of whom died in infancy with none living longer than two months. In 1640, the death of Rembrandt's mother added to their grief. In September 1641, Saskia gave birth to another son, Titus, who was the only one of their children to survive into adulthood. Sadly, however, in June the following year, weakened by the heartbreaking trials and tribulations of her successive pregnancies, Saskia died from tuberculosis.

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606 -1669)

'A Woman Bathing in a Stream', 1654 (oil on oak panel)

In 1643 Rembrandt employed Geertge Dircx as a nurse for Titus. As time passed their feelings for one another grew more intimate and she took up residence as his common law wife. However, in 1649 when Rembrandt introduced Hendrickje Stoffels as his new housekeeper, their relationship fell apart as the artist began an affair with his new domestic servant. This resulted in an acrimonious break up where Geertge sued Rembrandt for 'breach of promise' to marry her, and Rembrandt counter-sued as she had pawned some of Saskia’s jewellery that belonged to Titus. After a prolonged exchange of accusations and demands, Geertge refused to accept the final settlement and continued her impassioned petitions for adequate maintenance. In a vindictive action to put an end to the bitterness, Rembrandt had her locked up in the Gouda Spinhuis, a female house of correction, so-named as the inmates spent their days spinning yarn. In the meantime, Rembrandt and Hendrickje lived on happily as husband and wife but they were never able to marry, for according to the terms of Saskia's will, they would lose her inheritance if Rembrandt remarried. Nevertheless, they conceived another daughter, Cornelia, who was born in 1654 and the only one of Rembrandt's children to outlive him.

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606 -1669)

Detail from 'A Woman Bathing in a Stream', 1654 (oil on oak panel)

A 'Woman Bathing in a Stream' is a small intimate painting modelled on Hendrickje in the guise of a biblical figure such as Bathsheba or Susanna. It differs from the more precise technique of Rembrandt's earlier work in the strength and speed of its impasto [1] brushwork. The folds of her chemise are rendered with such masterful economy that just a few swashbuckling strokes define the gathering of the material as she lifts it clear from the water. Her hands are as skillfully conveyed in a handful of brush stokes as in any crafted passage of painting. Rembrandt, running counter to the growing fashion for fine detail and a polished finish, reflects the sensuality of the subject in the physicality of his paint, audaciously affirming the artistic value of spontaneity over refinement.

This is a key work that highlights the artist's exhilarating technique and heralds the unrestrained approach that characterizes the art of his remaining years. It is a personal picture for Rembrandt's own pleasure, but it also makes a personal statement about where he stands in relation to the art of his own time. Inured by his personal tragedies and bored with much of the superficiality he sees in the art of his contemporaries, he unashamedly tells the truth about the human condition to celebrate the unpretentious side of our nature.

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606 -1669)

Detail from 'A Woman Bathing in a Stream', 1654 (oil on oak panel)

Rembrandt switches from a thick impasto to thin glazes of color as he employs the full spectrum of oil painting techniques to create Hendrickje's skin and the surface of the water. Her flesh is rendered with a fluid range of tints that graduate from dark translucent tones to more opaque highlights. Glazing was traditionally a slow and methodical painting technique where colors and tones are built up in successive transparent layers, each allowed to dry before the application of the next. The oily glazes that Rembrandt uses to capture her reflection in the stream show the same unerring confidence and speed of application as his impasto technique. The fearless control that he exercises over his medium is astonishing. The German impressionist, Max Liebermann, summed it up well when he said: "Whenever I see a Frans Hals, I feel like painting; whenever I see a Rembrandt, I feel like giving up."

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606 -1669)

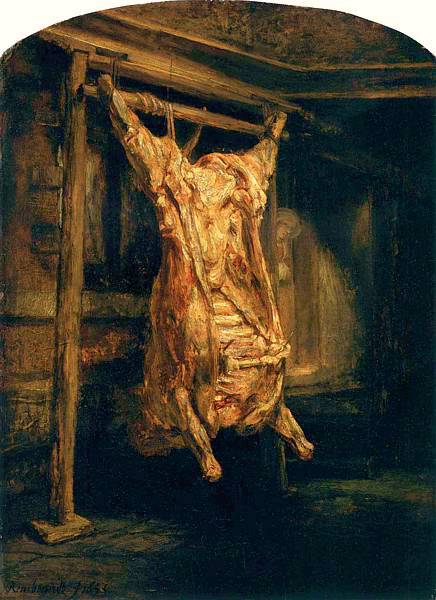

'The Slaughtered Ox', 1655 (oil on panel)

The Slaughtered Ox' is a powerful painting of a hanging carcass that has been cleaved down the middle to reveal its disembowelled innards. The physicality of Rembrandt's paint mimics the carnage of butchered flesh as he smears on thickly laden brushstrokes to build up the fat, flesh and bone of its grotesquely splayed form.

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606 -1669)

Detail of 'The Slaughtered Ox', 1655 (oil on panel)

The meaning of the work invites a range of different readings. Is it simply the depiction of a dead ox which has been hung to improve the flavour of the meat or is it a carnal image with spiritual and metaphysical overtones. Does it represent the fatted calf from the 'Parable of the Prodigal Son'? Is it a sacrificial or crucifixion metaphor, tortured and martyred on a wooden rack? Is it an allegory of youth and decay or innocence and corruption as the young girl peeks round the doorframe to gaze upon 'the way of all flesh'? Is it a vanitas still life that has been converted to a Dutch genre painting by the addition of her figure?

In the 1650s, Rembrandt was painting more for himself and less for his patrons. His spirited painting style was too eccentric, and the documentary realism of his work was too authentic for their conservative taste. Consequently, the demand for his paintings decreased and he suffered a drop in his income. With the additional strain of his extravagant lifestyle and his many years of financial mismanagement, he spiralled into a level of debt that he could not manage. To try to avoid the scandal of bankruptcy, he came to an arrangement with the court to liquidate his vast collection of drawings, paintings prints and antiques. They were disposed of at vastly reduced prices in two auctions of 1657 and 1658, but failed to raise enough to honour his debts, forcing him to sell his magnificent home.

Rembrandt was allowed to stay on at Sint Antoniesbreestraat until the end of 1660, at which time he moved to more modest accommodation in the Rosengracht, a poorer district on the other side of the city. His insolvency compelled him to live more frugally in a working-class neighborhood, but this simpler lifestyle, free from the burdens of ownership and possessions, seemed to liberate his spirit and revive his enthusiasm for his work. In 1661 he produced more finished paintings than at any time since the 1630s.

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606 -1669)

'The Prodigal Son', 1642 (pen and wash)

The 'Parable of the Prodigal Son' (Luke 15:11-21:22) is a subject that must have strongly resonated with Rembrandt, as he drew, printed and painted several episodes from it over the years. In the parable the father is a metaphor for God's unconditional love and the younger son represents our access to this healing relationship no matter how self-indulgent or sinful we have been. In some ways Rembrandt's own boom and bust lifestyle corresponds to the extravagant behaviour of the prodigal son and its redemptive message probably brought him some comfort.

This pen and wash drawing of 'The Prodigal Son' captures the repentance of the younger son and the forgiveness of the father with a remarkable economy of means. In the little boy on the left, a few impromptu lines are all it takes to convince us of his interest in this emotional reunion. His inclusion is inspired because it expands the narrative to suggest the son's return to a wider community and not just a private reconciliation with his father. There are very few artists in the history of art who come close to the effortless control and impact of a Rembrandt drawing.

'Rembrandt and Saskia in the Parable of the Prodigal Son'

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606 -1669)

'Rembrandt and Saskia in the Parable of the Prodigal Son', c.1637 (oil on canvas)

Rembrandt painted two works that personify the parable; one from the prosperous beginning to his career and one from its insolvent end. In the earlier painting of 'Rembrandt and Saskia in the Parable of the Prodigal Son' from 1637, the artist and his young bride pose as the son and his harlot in a brothel, raising a hedonistic toast to the high life. Although the scene is taken from a story with a moral message, there is no appropriate note of caution to reflect that lesson. What we are witnessing is Rembrandt’s unconscious celebration of his own success. The great irony of the painting is that it illustrates his own prodigal road to perdition through his addictive extravagance and reckless neglect of his finances.

'The Return of the Prodigal Son'

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606 -1669)

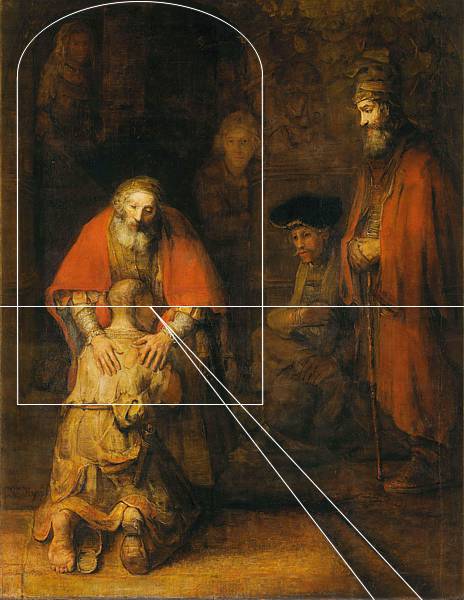

'The Return of the Prodigal Son', c.1667 (oil on canvas)

Where the early painting is immature and uninspiring, both morally and aesthetically, the later work 'The Return of the Prodigal Son' is a great Baroque masterpiece.

Rembrandt depicts the scene where the prodigal son returns to his father's house: he arrives dressed in rags with his head coarsely shaven as a mark of his sorrow; his eyes are red and swollen from crying as he drops to his knees to plead for forgiveness; one of his sandals falls off to reveal the bare sole of his foot, a symbol of his humility. In response, the father is greatly moved by his son’s remorse and compassionately embraces him.

Rembrandt places as much emphasis on the father's forgiveness as he does on the son's remorse. After Hendrickje died in 1663, he was more acutely aware of his own mortality as he approached his final years and the idea of exploring the concept of unconditional forgiveness was a naturally attractive proposition.

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606 -1669)

Composition of 'The Return of the Prodigal Son', c.1667 (oil on canvas)

The artist uses all his compositional skills to direct our attention to the relationship between the father and son. The archway at the back of the scene acts as a frame to focus our attention on them. He then uses the perspective of the floor to lead us directly to the eye-level of the son, which if you know your perspective drawing is also the eye-level of the viewer, thereby physically linking us to his plight. To consolidate the composition, 'chiaroscuro' (a dramatic contrast of light and dark tones) is applied to highlight their prominence while the others respectively fade into the background, subject to their significance.

The older son, dressed in a similar red cloak to his father, is the most obvious of the background figures and he brings his own moral message to the parable. The part he plays is to highlight the inclusiveness of the father's (God's) love for all, by contrasting it with his selfish sense of entitlement. His hard expression and folded hands reveal a lack of compassion towards his brother who he views as a threat to his position and inheritance. He mistakes the father's joy at the prodigal's return as a rejection of his faithfulness, while his jealousy and insecurity blind him to the wealth and good fortune he already possesses. As a result, he fails to see that his father loves him as much as his brother.

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606 -1669)

Detail from 'The Return of the Prodigal Son', c.1667 (oil on canvas)

If you are ever in doubt about the merit of a figure drawing or painting, look at the hands and feet as they are often the hallmark of its quality. Great artists never overlook their expressive value. The hands in Rembrandt's paintings always have an articulate authority. Sometimes they are overtly demonstrative like the gesture of Captain Banning Cocq in 'The Night Watch' while on other occasions they are covertly subtle. If you look closely at how the father embraces the son, you will notice a difference between his two hands. The hand on the right is more powerful and masculine while the one on the left has a more delicate feminine quality. With no mention of a mother in the original parable and only a possible hint of her existence in the faded figure at the back of the archway, Rembrandt expresses the breadth and depth of parental love by combining both male and female characteristics in the embrace of the son.

In most cultures, the exposure of bare feet is a sign of humility or subjection, either self-imposed or enforced. Footwear is often seen a symbol of status and the prodigal son's missing sandal represents his readiness to be accepted back as a humble servant. It is hard to think of a more expressive foot in art than the weary sole of Rembrandt's prodigal son.

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606 -1669)

Detail from 'Portrait of the Artist', c.1665 (oil on canvas)

Rembrandt's late self-portraits are his most sensitive works. He takes such an honest and unflinching look at his own decline through the decrepitude of his aging face that they force us to confront our own mortality. They express a deep melancholy and vulnerability that comes from acknowledging the darker aspects of our character, but they also have an enduring fortitude that comes from owning the imperfections we see there.

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606 -1669)

Detail from 'Portrait of the Artist', c.1665 (oil on canvas)

It has been suggested [2] that Rembrandt only used a mirror during the formative stages of his self-portraits to establish a basic likeness. He would then cover the mirror with a cloth and continue to paint, trusting in a lifetime's experience, until he arrived at a version of himself that he recognized as the truth. The resultant surface of these late works is rich in character, encrusted with layers of paint that chart his struggle to reach that point of resolution.

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606 -1669)

'Portrait of the Artist', c.1665 (oil on canvas)

Despite the personal tragedies and financial hardship of his final years, Rembrandt maintained his dignity as a person and integrity as an artist. The freedom of his painting technique generated a depth of expression that was so far ahead of its time that it would not be fully appreciated until the 19th century.

In his 'Self Portrait of the Artist' from 1665, Rembrandt presents us with a proud image of the artist, resplendent in a fur lined robe, holding the tools of his trade. His painting technique is increasingly free and fluent as it merges into the bulk of his body, his palette and paintbrushes no more than a sketchy impression. However, this broad technique effortlessly comes together and consolidates in the dramatic tones and rich textures of the head, a unique composite of the honesty, experience and unsurpassed ability that rises above the fluctuations of fashion and style and continues to endear Rembrandt to successive generations.

Rembrandt van Rijn Timeline

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606 -1669)

'Young Woman Sleeping' (Hendrickje Stoffels) 1654, brush drawing.

Rembrandt died, aged 63, on October 4th, 1669 and was buried beside Hendrickje and Titus in an unmarked grave in the Westerkerk, the largest Protestant church in the Netherlands. He was a man of the people, at home with the imperfections of the human condition – a quality that endears him to a modern audience but was not so attractive to his contemporaries who favoured a more refined approach to art. This was an attitude that prevailed until the growth of Romanticism in the 19th century, when artists were encouraged to express their innermost feelings about a subject. In 1851, Delacroix enraged the artistic establishment by voicing the opinion that one day Rembrandt could be considered a greater painter than Raphael. Within 50 years, his prediction was true.

-

1606 - Rembrandt is born in Leiden.

-

1620 - Studies at Leiden University.

-

1624-25 - Sets up a studio in Leiden with Pieter Lastman.

-

1631 - Moves to the studios of Hendrick van Uylenburgh in Amsterdam. Attracts more clients with his 'Portrait of Nicolaes Ruts'.

-

1632 - Paints 'The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Tulp'.

-

1634 - Marries Saskia van Uylenburgh.

-

1635 - Paints 'Saskia van Uylenburgh in Arcadian Costume'.

-

1635-40 - Successive infant deaths of three of their children.

-

1637 - Paints 'Rembrandt and Saskia in the Parable of the Prodigal Son'.

-

1640 - Rembrandt's mother dies.

-

1641 - Birth of a son named Titus.

-

1642 - Death of Saskia. Paints his masterpiece, 'The Night Watch'.

-

1643 - Geertge Dircx employed as a nurse.

-

1647 - Hendrickje Stoffels employed as maid and becomes Rembrandt's mistress.

-

1654 - Paints 'A Woman Bathing in a Stream'. Hendrickje gives birth to a daughter Cornelia.

-

1655 - Paints 'The Slaughtered Ox'.

-

1656 - Rembrandt declared insolvent.

-

1661 - Paints 'The Syndics and Oath of Julius Civilius'. Paints 'Self Portrait as the Apostle Paul'.

-

1663 - Death of Hendrickje Stoffels.

-

1665 - Paints 'Self Portrait of the Artist'. Paints 'The Jewish Bride'.

-

1667 - Paints 'The Return of the Prodigal Son'

-

1668 - Death of Titus.

-

1669 - Rembrandt dies in Amsterdam.