Italian Renaissance Art - Oil Painting

During the Italian Renaissance, oil painting replaced both tempera and fresco as the primary painting medium used by artists.

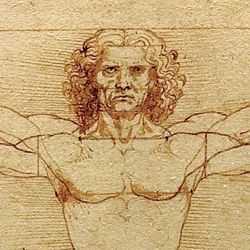

LEONARDO DA VINCI (1452-1519)

'The Virgin of the Rocks', 1483-85 (oil on poplar panel)

Oil painting replaced both tempera and fresco as the principal painting medium of the Italian Renaissance. It produced the most intense color, the greatest tonal range and a workable drying time that allowed the artist to render the finest naturalistic detail possible.

Leonardo, one of the first great masters of the technique, exploited all these qualities in his paintings. Due to its versatility, oil paint allowed him to create unprecedented subtlety of tone in the rendering of the flesh and form of the human figure and enabled him to paint the exquisite details of plants and rocks that displayed his scientific knowledge of botany and geology.

JAN VAN EYCK (1390-1441)

'Portrait of a Man in a Turban', 1433 (oil on panel)

Early Renaissance artists were aware of the limitations of fresco and tempera painting techniques. The two main issues were that these media were quick drying making it difficult to blend tones and the vibrant pigments used to mix the medium lost their intensity of color in the process of applying the paint.

The solution to these problems came from the art of Northern Europe and, in particular, the great Flemish master, Jan van Eyck. Some artists had experimented with oil based varnishes to lift the vitality of their colors but with no great success. Paintings that were finished with these slow drying varnishes had to be left out the sun to dry, often cracking or blistering in the heat. In an attempt to develop a varnish that dried indoors, Van Eyck discovered that linseed and walnut oils dried faster than any others he tested. Furthermore, when he tried mixing them with his pigments, he saw that his colors were so vibrant that they no longer needed a final varnish. They were also waterproof when dry, with a smooth consistency that blended infinitely better than tempera or fresco.

Van Eyck developed an exceptional technique with oil paints to create superbly naturalistic images with brilliant glowing colors. His stunning detail, lifelike textures, subtle blends and dramatic contrasts of tone gained him an unrivalled reputation throughout Europe. This portrait is considered by many sources to be a self portrait of the artist.

Oil Painting in Venice

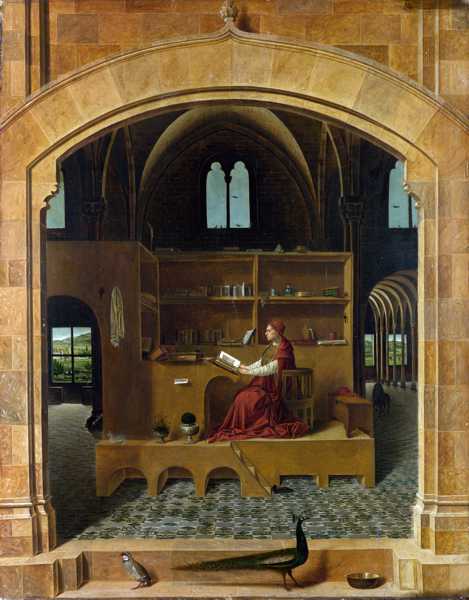

Antonello da Messina (c.1430-79)

'St. Jerome in His Study', 1474-75 (oil on panel)

Antonello da Messina (1430-79), a Sicilian born artist was inspired by the outstanding qualities of Flemish art. There are various speculative explanations as to how Antonello acquired his knowledge of the Flemish painting technique, but his influence had a pivotal effect on the style of the great Venetian painter, Giovanni Bellini, whose paintings introduced the colorful and atmospheric characteristics we have come to associate with Venetian Renaissance art.

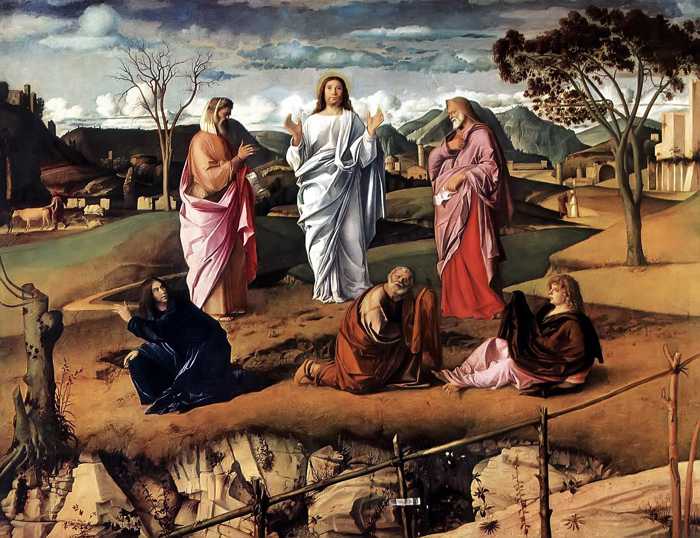

GIOVANNI BELLINI (1430-1516)

'The Transfiguration of Christ', 1480 (oil on panel)

Giovanni Bellini, the major artist in Venice at the time of Antonello's arrival, was hugely impressed by the fluency of Flemish oil painting and adapted the technique for his own work. The advantages of oil paint over other techniques were its slow drying time and its translucency. Its slow drying time allowed artists to broaden their brushstrokes and blend transitions of tone and color to a smoothness that was previously unachievable. Its translucent qualities allowed them to focus on the tonal under-painting to establish a composition that was modelled in light, over which they would apply transparent glazes of color to create a radiant jewel-like finish.

We see all these qualities in Bellini's painting of 'The Transfiguration of Christ', one of his first experiments with oil paint. This work depicts an extraordinary scene (Mark 9:2-13) where the human meets the divine: when Christ, together with Moses and Elijah, is glimpsed in his heavenly glory by the apostles, Peter, James and John. "He (Peter) did not know what to say, for they were terrified. Then a cloud overshadowed them, and from the cloud there came a voice, "This is my Son, the Beloved; listen to him!"

The visual metaphor that Bellini uses to capture the mystical aura of this event is that eerie sunlight you encounter when the air bristles with static electricity just before the arrival of a thunderstorm. The advancing storm clouds above Christ also symbolize his approaching passion and death on the cross. This charged atmosphere of dramatic light, glowing color and naturalistic textures does remarkable justice to this spellbinding scene.

GIOVANNI BELLINI (1430-1516)

'Detail from Portrait of Doge Leonardo Loredan', 1501 (oil on panel)

Although oil painting evolved in Northern Europe, it matured as a medium in Venice. We can see the range of its development if we compare two portraits of the Doges of Venice by Bellini and his pupil Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), who dominated Venetian painting for 60 years after his master's death.

In the Bellini portrait, the aim is to create as naturalistic likeness as possible. The smooth surface of the Doge's skin and the luxurious texture of his silk brocade jacket are stunningly rendered in meticulous detail. In painting the portrait, the artist constructs the work in three basic stages:

-

Over a thinly painted drawing Bellini develops the depth of color in the skin, the unadorned areas of fabric and the background with translucent layers of color.

-

Then he picks out the drawing of the decorative thread work and other small details in more opaque colors using very fine brushes.

-

Finally, he builds up the tonal form of the figure with dark transparent glazes and opaque highlights to unify all the elements of the image.

Titian (c.1490-1576)

'Detail from Portrait of Doge Marcantonio Trevisani', 1553-54 (oil on canvas)

In the Titian portrait, we have a broader painting technique that exploits the natural qualities of oil paint for expressive effect. Where Bellini disguises his brushstrokes for illusionistic impact, Titian embraces the tactile qualities of the medium and uses them as an element that reflects his personality as an artist. What his paintings lose in terms of detail, they gain in spontaneity. Titian’s breath-taking brushwork has a vitality and beauty of its own, irrespective of what it represents. In his painting of the Doge, we see the full potential of oil paint: a fluid and malleable medium that is applied both thinly and thickly to create a depth of color and variety of textures. Titian's technique expanded the creative potential of oil painting and laid the foundations for a more expressive approach to art in the centuries ahead.

Oil Painting in Florence

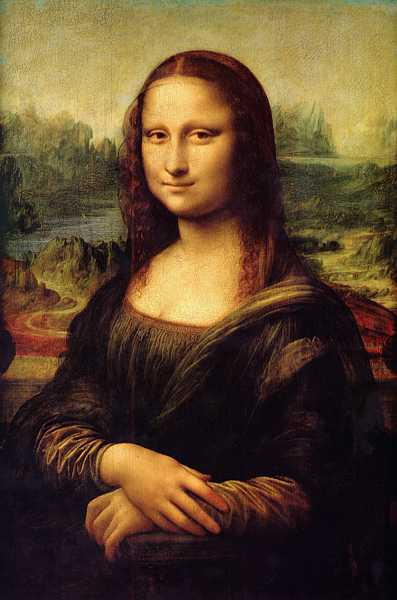

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519)

'Mona Lisa', c.1503-06 (oil on panel)

Oil painting in Florence followed the more precise style of Bellini that advocated greater naturalism with a stronger emphasis on the accuracy of drawing. Leonardo da Vinci took this approach to the ultimate level when de developed a technique called 'sfumato'.

The term 'sfumato', which translates as 'smoky', refers to a blurring of the hard edge lines that separate adjacent objects or colors from one another. It gives the image a greater naturalism by suggesting those imperceptible movements of energy that exist in the living form. This technique only became possible through the slow drying time of oil paint as it takes considerable time to blend the edges in such a subtle manner.

You can see the 'sfumato' effect throughout Leonardo's painting of the 'Mona Lisa' in the blurred outline of her form against the hazy landscape and in the softening of features in her face and hands.

Raphael (c.1483-1520)

'Saint Catherine of Alexandria', c.1508 (oil on panel)

Raphael admired the unity that 'sfumato' brought to Leonardo's work but felt that it suppressed color in favour of tone. He was aware that Michelangelo had developed cangiantismo to combat a similar problem with fresco and tempera. Consequently, he adapted the 'sfumato' technique to form his own version which he called 'unione', a 'union' that brought tone and color together in a more equal relationship. Where 'sfumato' blurred the outline of a form with dark or light tones, 'unione' did the same using more intense hues, thereby retaining the glowing colors we have come to associate with oil painting in the Italian Renaissance.