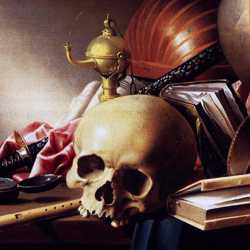

Vanitas Still Life by Harmen Steenwyck

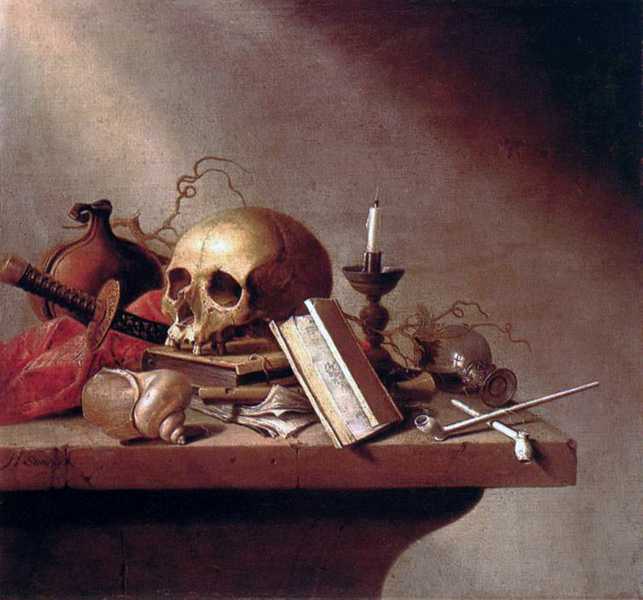

Harmen Steenwyck was a Dutch still life painter. His masterpiece 'Still Life: An Allegory of the Vanities of Human Life' is the classic example of a Dutch vanitas painting.

HARMEN STEENWYCK (1612-1656)

'Still Life: An Allegory of the Vanities of Human Life', 1640 (oil on oak panel)

Still Life: An Allegory of the Vanities of Human Life' by Harmen Steenwyck is a classic example of a Dutch 'Vanitas' painting. It is essentially a religious works in the guise of a still life. 'Vanitas' paintings caution the viewer to be careful about placing too much importance in the wealth and pleasures of this life, as they could become an obstacle on the path to salvation. The title 'Vanitas' comes from a quotation from the Book of Ecclesiastes 1:2, 'Vanity of vanities, all is vanity.'

The Symbolism of Vanitas Objects

The objects in this painting have been chosen carefully to communicate the 'Vanitas' message which is summarized in the Gospel of Matthew 6:18-21: “Do not store up for yourselves treasures on earth, where moth and rust destroy, and where thieves break in and steal. But store up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where moth and rust do not destroy, and where thieves do not break in and steal. For where your treasure is, there your heart will be also."

Each object in the picture has a different symbolic meaning that contributes to the overall message:

The skull, which is the focal point of the work, is the universal symbol of death. The chronometer (the timepiece that resembles a pocket watch) and the gold oil lamp which has just been extinguished, mark the length and passing of life.

The shell (Turbinidae), which is a highly polished specimen usually found in south east Asia, is a symbol of wealth, as only a rich collector would own such a rare object from a distant land. Shells are also traditionally used in art as symbols of birth and fertility.

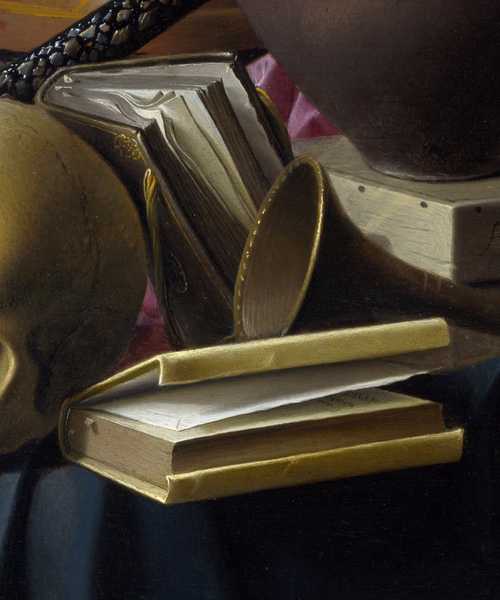

The books represent the range of human knowledge, while the musical instruments suggest the pleasures of the senses. Both are seen as luxuries and indulgences of this life.

The purple silk cloth is an example of physical luxury. Silk is the finest of all materials, while purple was the most expensive colour dye.

As a symbol, the Japanese Samurai sword works on two levels. It represents both military power and superior craftsmanship. These razor edged swords, which were handcrafted to perfection by skilled artisans, were both beautiful and deadly weapons.

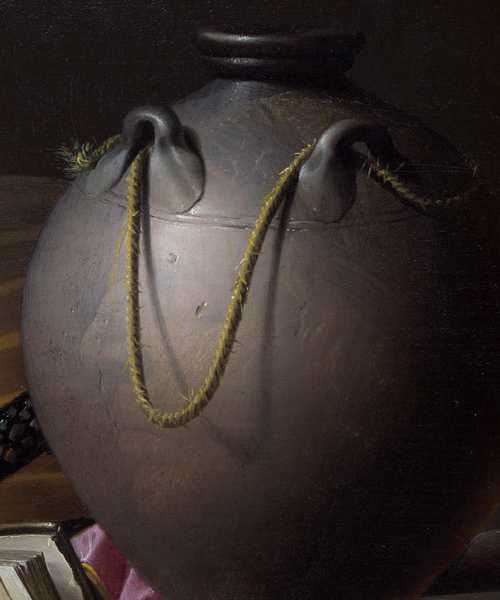

The stoneware jar at the right hand edge of the picture probably contained water or oil; both are symbolic elements that sustain life. Over the centuries, however, the oil paint that the artist used has become transparent and if you look closely you will see that it is starting to reveal the bust of a Roman emperor painted beneath the jar - you can see its nose and mouth just to the left of the rope handle. This shows a change to the composition that the artist has made during the painting of the still life. At some stage of the work he decided to swap the more complex form of a sculpted bust for the simpler form of a stoneware jar. This was probably because the Roman emperor was too dramatic an image to be placed at the edge of the arrangement as it detracted from the importance of the skull as the painting's focal point.

Steenwyck's Symbolic Composition

Steenwyck has used the diagonals to construct the composition.

The composition of the work also amplifies the still life's symbolic meaning. In our illustration you can see how Harmen Steenwyck has used the diagonals of the painting to construct its arrangement. The objects which represent the 'Vanities of Human Life' fill the lower half of the work. The absence of form in the upper half represents our spiritual existence. It is an empty space into which we can project our beliefs and ideas as to what this means. In this space a beam of light, which descends on the opposite diagonal, establishes the dramatic tone of the work and symbolically suggests the link between this life and the next. This beam also has two practical functions within the composition: it illuminates the skull and acts as a counterbalance to the triangular arrangement of objects in the lower section.

Steenwyck's Painting Technique

Thin glazes of oil paint realistically convey a wide range of textures.

Steenwyck employs a very impressive painting technique to give the still life a vivid sense of realism. Using small brushes, he paints the image on an oak panel which is primed and sanded to form a glass smooth ground. By building up the picture with thin glazes of oil paint he manages to realistically convey the wide range of textures that the individual objects possess: the iridescence of the shell, the translucence of bone, the softness of leather, the smoothness of silk, the reflections of metal, the coldness of stoneware, the roughness of rope and a variety of wood surfaces that range from a gloss varnish to a dull matt.

The assorted forms and textures of the objects are unified by the limited palette of tertiary colours that Steenwyck selects. These subdued colours are chosen because the overall arrangement of objects is too complex and their textures are too refined to support a bolder colour composition. To counteract this subtlety he adds a sense of drama by highlighting each object with exaggerated tone.

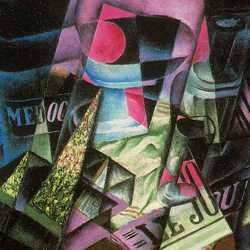

The Development of Dutch Still Life

HARMEN STEENWYCK (1612-1656)

'Still Life with Fruit and Dead Fowl', 1630 (oil on canvas)

In seventeenth century Holland, still life grew in popularity as a subject due to the Reformation. In the previous centuries artists had found patronage in the creation of religious imagery for the Catholic Church, but as this support declined, they had to adapt to survive in the new Protestant climate. Still lifes, using symbolic images that reflected Protestant attitudes, found favour and patronage from the Dutch merchant classes. The character of different towns is even reflected in their choice of symbolic objects. The university town of Leiden, where Harmen Steenwyck studied art under his uncle David Bailly, preferred skulls and books, whereas the Hague, a market centre, favoured fish with its traditional Christian associations, while many others used flowers, another Dutch product.

The Vanitas Influence

DAVID BAILLY (1584-1657)

'Self-Portrait with Vanitas Symbols', 1651 (oil on wood panel)

David Bailly was Harmen Steenwyck's uncle and teacher. You can see his influence through the choice of subject matter in his painting below. This is a self portrait of Bailly with a full range of 'Vanitas' objects. The painting depicts Bailly as a young man holding a contemporary self portrait - he was in his sixties when he painted the work. This gesture fuses together portraiture and still life into the one 'Vanitas' concept.

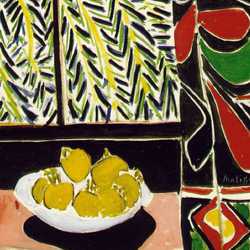

The Vanitas Contradiction

HARMEN STEENWYCK (1612-1656)

'Vanitas', 1640 (oil on wood panel)

Vanitas paintings were popular in countries with strict Protestant and Catholic Christian principles such as Holland and Spain. They were purchased by the rich who possessed a conscience about the wealth they had accumulated. However the genre had an in-built contradiction in the irony that the paintings were also valuable and collectible commodities and, as such, became 'Vanitas' objects themselves.

Harmen Steenwyck Notes

HARMEN STEENWYCK (1612-1656)

'Still Life of Game, Fish, Fruit and Kitchen Utensils',

(oil on panel)

Harmen Steenwyck was a Dutch 'Vanitas' still life painter. He was born in Delft (c.1612) and lived most of his life there, apart from a trip to the East Indies (1654-55).

-

'Vanitas' paintings were warnings that you should not be concerned about the wealth and possessions you accumulate in this world as you can't take them with you when you die.

-

Vanitas still lifes depicted objects that had a symbolic meaning: a skull as a symbol of death, a shell as a symbol of birth or books to represent knowledge.

-

Harmen Steenwyck was from the university town of Leiden where artists often used skulls and books as 'Vanitas' objects. You can recognise works from other towns by their specific selection of symbolic objects.

-

Harmen Steenwyck paints his images with incredible realism and astonishing skill. This realism is meant to enhance the truth of the 'Vanitas' message.

-

Ironically the 'Vanitas' style had an obvious in-built contradiction: the paintings were expensive collectable commodities and as such became Vanitas objects themselves.

-

Harmen Steenwyck died in 1656 in Leiden, the town where he first worked as an artist.